Venture, battery software and… coffee? (part 1)

Welcome to Long Form February! We’ve got some longer pieces for you this month, devoting a bit more text to a couple of things we thought needed a deeper dive. Starting with Gaël’s take on venture and software, you’ll want a coffee for this one…

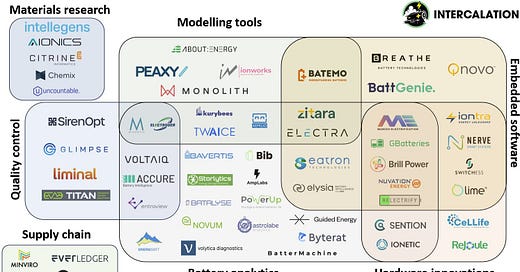

Last year, in part 2 of our series on battery software I looked into the battery software market. In particular, I made a graphical overview of many startups active in the field of battery software, from applying machine learning to material research to developing next-gen Battery Management Systems (BMS). Here is a 2025 up-to-date version (don’t hesitate to suggest more if you notice some are missing) :

In part 3, I explored where I thought the battery software market was going. I briefly touched upon the topic of hardware+software vs. pure Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) business models. Since then, there have been some interesting things written on deep tech and vertical integration, so I thought I’d go more in-depth on that topic.

What does “venture-scale” mean?

The software love story

Deep Tech and risk

Vertical Integrators

A parallel with coffee

The potential of vertical integration in battery software

What is a venture-scale company?

What I am most interested in, is what make a company “venture-scale” in the world of battery software. But what is venture scale?

I liked the definition given by Byrne Hobart in The Riff episode 51 with Erik Torenberg: “venture-scale” is a business that has the potential to be worth 20x or more after dilution, and return the entire fund of the venture capitalists who invested in it (by this, I mean that if their entire fund is 500M, they expect their 20M investment in that one startup to moonshot to 500M+).

The Software love story

For the past few decades, the common wisdom was that Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) was the best business model for venture-scale companies. It's the core idea of influential essays of the 2010’s, such as Marc Andreessen's Software is eating the world (2011) and Ben Thompson's Aggregation theory (2015) : in a nutshell, that software-centric startups like Amazon, Google, Facebook, Uber, Airbnb were able to create value not by controlling the supply of physical resources (cars, apartments, books, newspapers…) but rather aggregating them. It's easy to see what made them “venture-scale”: low upfront capital cost, huge disruptive potential, and a winner-takes-all situation thanks to network effects.

This common wisdom also influenced VCs investing in climate tech and batteries. In a recent episode of Redefining Energy entitled “Top trends in Climate tech”, Dr. Caroline Funk, partner at Blue Bear Capital (a silicon Valley VC firm that invested in Accure), affirms that:

At the Venture scale, we believe that software and data are going to provide the biggest returns.

Deep Tech and risk

In Why there won’t be any new aggregators (2019) however, Packy McCormick argues that all good things come to an end. In parts, because aggregating demand and supply for resources that already exist is mostly an allocation/information problem. One that can be solved by software, and has been (for the most part). The logical consequence would be that internet-inspired asset-light solutions will see diminishing returns over time.

The opposite of these asset-light solutions can be broadly referred to as “deep tech” (as opposed to “shallow tech”). The difference is not so much in terms of assets (hardware versus software, although deep tech startups tend to have an important hardware component) but rather in terms of risks. This is explained in No market risk by Francesco Ricciuti (2024) : SaaS startups undergo “market risk” (is there a market for the solution?). Deep tech startups, on the other hand, also need to take technical and execution risk (is the solution technically feasible, and can it reach the market?)

A generation of investors who grew in the software era is simply not ready to underwrite [technical and execution] risk.

In A financial argument for deep tech (2022) Ian Rountree defends a similar idea round the notion of “deep tech” (startups taking technical risk rather than market risks):

from 2012 through 2016 […] I avoided hardware and biology startups because all the smart VCs I looked up to said things like “hardware is hard”. […] Most of what we invest in at Cantos nowadays is either making commodities cheaper and with a lower carbon footprint. […] there’s less risk than you might think at first glance. It’s just a different type of risk.

It’s true that while pivots can be harder when you build hardware or biotech, the moats you can dig for yourself can also be deeper (by “moat” I mean the thing preventing other companies from doing the same at a lower price and winning away customers). There’s a good argument to be made that a company that aggregates the advantages of both hardware (deeper moats) and software (fast iteration) might define the venture-scale of the 2020’s.

Vertical Integrators

That’s the main thesis of the series “Vertical Integrators” by Packy McCormick. In part 2 of his series he has some interesting examples of startups pulling off the integration of both hardware and software elements. In the manufacturing sector, there is the example of Hadrian, which started as SaaS for manufacturing (like Oden technologies) but pivoted towards building from the ground up.

I realized that the right way to bring technology to the industrial space is not to sell software to these companies, it’s to build an industrial business from scratch with software.

It seems to be working. Hadrian is worth roughly $500 million and expects to reach $30 million in revenue as a three-year-old company. In the mining sector, there is the example of Earth AI, which initially developed AI software for mining companies, but pivoted towards integrating the software to its own hardware optimized for it:

The two work together – not just AI, not just hardware, but a combination of the two that gives Earth AI advantages in accuracy, speed, and cost. Instead of selling software to explorers, Earth AI is an explorer, and a driller. It discovers new deposits more efficiently, and drills to prove out those deposits more quickly, than traditional explorers and drillers can.

Earth AI made ~7% of the discoveries the whole industry made in 2023. A similar example can be seen with KoBold Metals, which raised half a billion in its most recent funding round. In the defense space, we could cite the example of Anduril, which recently won a $200M drone contract with the DoD:

We found that selling software was incredibly difficult. […]. Our focus was putting the thing we know DoD really needed, which was the software system/autonomy capability, and wrapping it in metal […]. We use that as a Trojan horse to get software in the front door.

And I think in battery software, there is a lot of potential in going the vertical integration route : getting better data through innovations in hardware, and using this data in a smarter way through innovations in software.

What may it look like? Let me explain with… coffee.

A parallel between battery software and coffee

Imagine traveling back to the 18th century, when the coffee market was in its infancy in Europe. The default way of processing coffee back then was to boil coffee beans in water, in copper or silver coffee pots. As a time traveler, you’d probably think “wait, I could make better coffee than this”. Somewhat similarly, the way we manufacture and operate batteries is pretty rough, and entrepreneurs in the battery software space are essentially thinking “wait, I could make better use of battery data”. This leads, in my mind, to the following parallel:

Back to the coffee market for a minute : how would you make money making and selling better coffee?

The first business model that would spring to mind would be the coffee shop model : if you had knowledge in preparing coffee you could sell ready-to-drink coffee to customers (like Caffè Florian founded in 1720).

The second business model, if you were more engineering-oriented, would be the coffee machine manufacturing model : designing machines that would perform better aroma extraction than just basic coffee pots for boiling beans (like the first espresso machine invented in 1822).

The third business model would be that of a coffee store model : buying raw coffee beans and selling them roasted/grinded in coffee packs (like the first Lavazza store in 1895). Especially if your customers have machines that require coffee to be grinded just right.

The parallel with batteries would be the following : in the same way that customers in the coffee market want a nice cup of coffee which is non-trivial to obtain from coffee beans, customers in the battery market want to access battery states that are non-trivial to obtain from raw operational data : it could be a state-of-charge or state-of-health, an internal resistance or a capacity, or the remaining useful life of the battery. So similarly to the coffee space, there are three main business models that emerge:

The equivalent of the coffee shop model would be to process customers data directly to deliver them battery states (cups of coffee) directly. This would be the cloud model.

The equivalent of the coffee machine manufacturing model would be to create more advanced equipment and electronics hardware (coffee machines), to improve the data that’s extracted from the batteries. This would be the hardware model.

And finally, the equivalent of the coffee store model would be to develop a software layer (roasted and grinded coffee beans) that’s custom-made for your customer’s hardware (their coffee machines). This would be the software layer model.

No framework is perfect, but we can actually tie most startups in this overview to these three types of business models:

Coffee Shop Model: Pretty much all startups in the “Battery Analytics” section, as well as the “Materials Research” category, and to an extent the “Supply Chain” category belong to the cloud model. For example, Voltaiq will create data pipelines and automatic treatment of various tests to help gigafactories gain insight from their data. TWAICE and ACCURE are active in the BESS space, where they provide dashboards that output state-of-charge and state-of-health of strings of batteries, with applications in predictive maintenance and warranty compliance.

Beans Roasting & Grinding: Pretty much all startups in the“Embedded Software” apply a software layer model. For example, the partnership between Breathe Battery Technologies and Oppo (state-of-charge and charging optimization for Oppo’s smartphones) or Elysia and Fortescue (fast-charging and path optimization for Fortescue’s electric trucks). You could see these companies as selling high-quality coffee, grinded perfectly for their customer’s machine. In the case of the “Modelling Tools” category, you could see that as one level down, like selling high-quality coffee beans that the customers still have to roast and grind themselves. About:Energy, for example, provides battery data and various electrochemical and thermal models that can be used for pack and system design.

Coffee Machine Model: And finally, startups in the “Hardware Innovations” and “Quality Control” usually have some form of hardware they develop to improve data collection. For example, Liminal develops ultrasound solutions for non-destructive sensing in battery manufacturing, while Relectrify develops its own BMS electronics for cell level control.

The potential of vertical integration in battery software: The Nespresso model

There's one important business model in coffee that I left out, however.

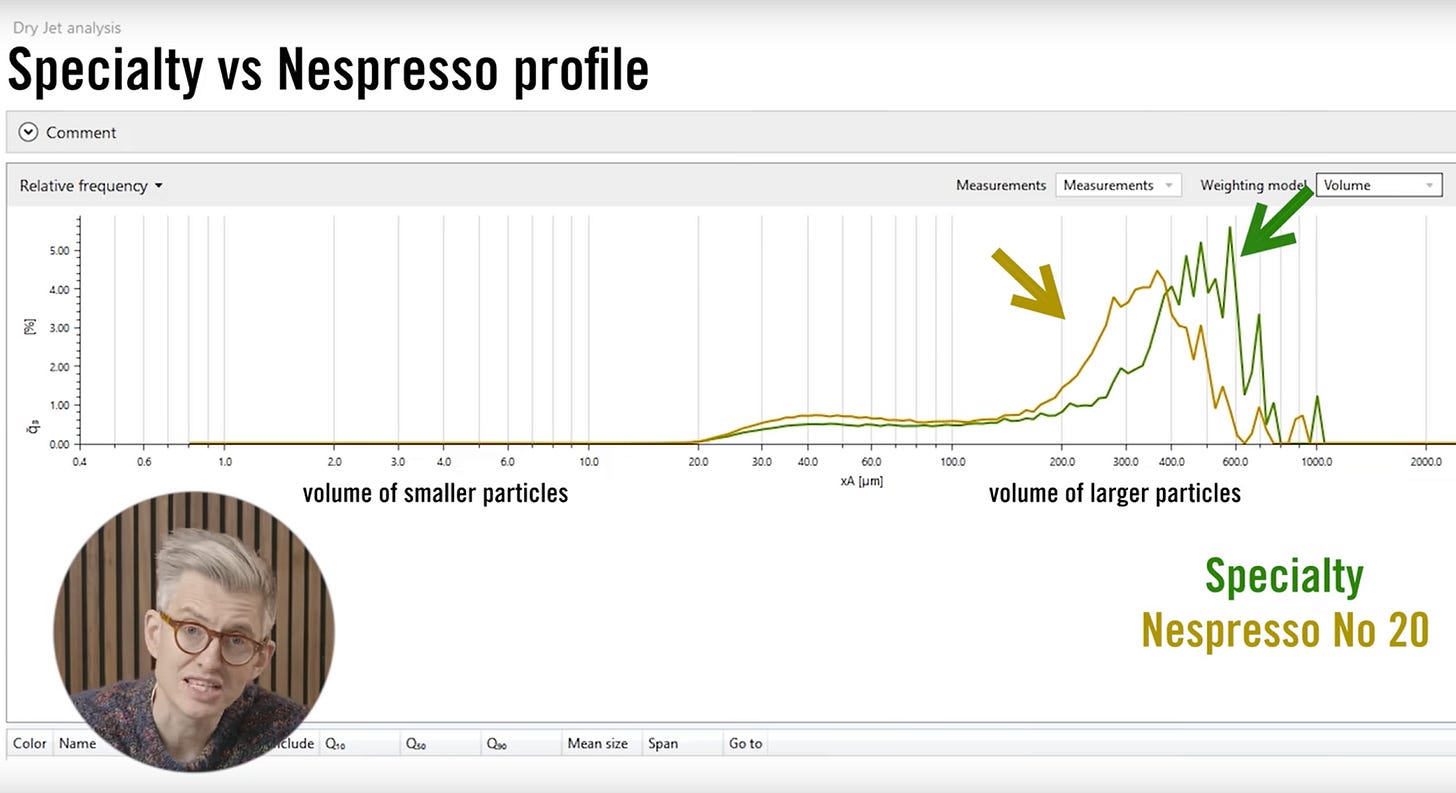

In the 1980s, Nestlé disrupted the three traditional business models of the coffee market with Nespresso, introducing the coffee capsules business model. The idea is that they sell coffee machines that work with capsules, containing a single dose of coffee each. The machines are sold for cheap (even at a loss sometimes), and most of the revenue is made through recurring capsule sales. When you dive in the details of the engineering behind the Nespresso way of making coffee (from how the coffee is grinded, to the rotation of the capsule in the machine, so that the coffee comes out with just the right amount of foam), it’s a really nice illustration of what is achievable when you control the complete process chain.

Nespresso may look like a machine manufacturer at first glance but it is actually a coffee reseller, which value proposition is to provide coffee shop-quality coffee at home. And I think it is a nice illustration of the difference between modularization and vertical integration in the coffee industry:

Regarding the previous examples of Earth AI and Anduril, i.e. software-centric startups that build tailor-made hardware, I think there’s an interesting parallel with Nespresso.

It’s maybe not so surprising that the most successful com panies in the battery space are vertically integrated : Tesla, BYD, CATL to name just a few companies that started with hardware/manufacturing and slowly integrated software elements (such as Tesla’s Autobidder software or CATL’s AB BMS for hybrid battery packs).

But is vertical integration the optimal strategy for a startup in the battery sector? This I will discuss in part 2!

🌞 Thanks for reading!

📧 For tips, feedback, or inquiries - reach out

📣 For newsletter sponsorships - click here