Apple announced they will use 100 percent recycling cobalt by 2025. Cobalt is notorious for human rights abuses in its supply chain, particularly in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and companies looking to stabilise their supply and avoid human rights criticisms are keen to follow Apple’s example. However, does this solve a problem, or does it avoid solving the problem?

Something often missing in these discussions is Congolese voices, particularly in English. Issy spoke to researcher Gérardine Deade Tanakula from the University of Kinshasha to understand how the cobalt industry shapes lives in the DRC and the path to a free Congo and ethical Cobalt supply chain.

At the end of January 2025, the rebel M23 group in the east of the DRC captured the city of Goma, killing over 3,000 people and displacing more than 110,000. This group is accused of trafficking Congolese minerals and selling them through Rwanda. Our thoughts and prayers are with the population of the DRC at this time.

Cobalt mining in the DRC is really complicated, so here we focus on:

What it’s like to be a researcher in the DRC, and how daily life intersects with the cobalt industry

Who supports the current status quo of cobalt mining and why

How the history of exploitation in the country still exists in daily life

How the privatisation of the mining industry still affects the population today

How the mining sector could be transformed for the Congolese society

How the DRC could add value to the economy by refining metals

What a vision of a ‘free congo’ would look like

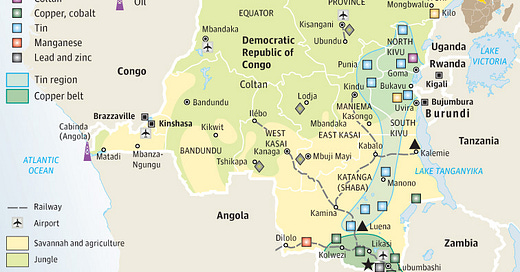

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a central African country home to 109 million people, and the main language spoken is French. It sits on the sedimentary basin of the Congo river, containing some of the largest tropical rainforest in the world. The country also has the world’s largest reserves of cobalt, which are found in the south east.

The DRC represents about 70% of the world’s supply of mined cobalt. Much of this cobalt ends up in various alloys, but many battery cathode chemistries like LCO, NCA, and NMC rely on cobalt for structural stability and energy density.

Even with predictions for NMC market share decreasing as LFP becomes the preferred chemsitry for EVs for cost reasons, the world will consume a lot of cobalt over the next few decades.

I’ve spent the last few years learning about supply chains, and part of that time working on cobalt-free cathode material. I’ve seen pictures of children in mines and followed the protest movements for a free Congo. To truly see the mineral in its context, I wanted to understand what life was like living next to this keystone of the global sustainability revolution, and I was lucky enough to speak to researcher Gérardine, who works in the capital Kinshasa.

I started by asking her to tell me about her research and life in the Congo.

Kinshasa is the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, one of the major economic, political, and cultural centres of Africa. Living and working here often involves adapting to the realities of a rapidly growing city of more than 15 million people. It is full of life, but faces some important challenges, such as in infrastructure development, access to public services, and economic inequality. “Kinois” – people who live in Kinshasa – are known for their resilience and creativity, showcased in areas like music (particularly Congolese rumba), art, and entrepreneurialism. Research is seen as something done only by poorer people with a passion for it.

I am a researcher in the field of international relations, specifically related to the environment and agriculture. My work focuses on Congolese arable land, and tries to understand the impact of agro-imperialism in the DRC. Food insecurity is rising rapidly as multinationals continuously exploit the Congo’s arable land. I work on water and food diplomacy, green diplomacy, and particularly on climate change.

Doing research in Kinshasa is not easy, especially when it is self-financed and data is opaque. Several channels are closed to us, and corruption means that no one wants their secrets to be disclosed. We use several different strategies to obtain data, which stretch our finances. Donors fund research projects that they themselves have outlined according to their goals and interests; anything that does not fit with their goals is not supported. As a scientist and activist, I am not ready to give in, so we push on despite the challenges.

The reality of being a researcher in the DRC sounds worlds away from my own research in the UK. Gérardine tells me a little more about her home.

In 2023, the DRC went from fourth to second in the ND-GAIN index1 of the most vulnerable countries to climate change. Put simply, we are the second least able country to deal with the impacts of climate change. That is very alarming. The government struggles to believe scientists – instead listening to the selfish interests of “climate vampires” – and is concerned with money to the detriment of its people. In addition, the history of greenhouse gas emissions [carbon accounting] here is very shady. Several companies use it to continue to pollute under the pretext of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Africa with reforestation projects, etc., which have no visible impact. Recently, in Kinshasa, we had severe flooding which caused the death of several children, parents, young people etc. It is disappointing: as scientists, having observed that our house is on fire, we are shouting about it in vain.

The picture painted to me was a vivid and fascinating one. Kinshasha is in the west of the country, away from the copper belt where Cobalt is mined. I wanted to understand how engrained the Cobalt industry was with her work, so I asked whether there was any intersection between the two.

Yes, in the sense that we deplore the consequences of the extraction of these cobalt companies on agriculture and the lives of thousands of people. Companies focus on their interests to the detriment of the Congolese people. We as Congolese have lots of resources; this has the potential to be a rich country – with the resources needed for the green transition, like lithium, cobalt, etc. – but it has a very poor and vulnerable population. The cobalt industry in the DRC has significant consequences, including:

Cobalt mining leads to massive deforestation, chemical contamination of soil and water sources, and destruction of natural habitats.

Working conditions in artisanal mines are often dangerous, with serious exploitation of workers, including children. It is a system of exploitation of man by man with minimal pay but excessive suffering. The industry is marked by human rights abuses, including forced labor and inhumane working conditions.

The cobalt trade has often been linked to armed conflicts, where armed groups exploit mines to finance their activities, exacerbating regional instability. This is not just about armed groups, but foreign actors who support them and encourage their cobalt extractions.

Resource management is often tainted by corruption, which hinders the economic and social development of the country.

Workers and surrounding communities suffer health problems related to exposure to toxic substances used in the extraction process. The Democratic Republic of Congo is a country exceptionally rich in minerals but today remains mired in poverty – 80% of the population has an income of less than two US dollars per day.

Since the consequences are enormous, quite a few DRC scientists work on this subject to report the abuses.

Particular armed groups such as M23 are mostly focused around the east of the DRC, around the tin, tungsten, tantalum, and coltan mining. In cobalt mining, the particular problem is around police forces intended to maintain security, where some members are involved in fraud and smuggling of raw materials.

Multinationals use chaos theory in the DRC. They create chaos and profit from it, while people in the international community (which includes themselves) expect them to find a solution to this chaos.

How can the creator and profiter of chaos ask himself to put an end to the same chaos, what do you expect the results will be? This is the case of the war in the east.

This complicated picture tallied with what I’ve read about the DRC. I wanted to understand who the actors are supporting this status quo, and Gérardine talked me through each aspect.

These groups can be composed of various actors, including workers, business leaders, political actors and sometimes members of the local community. There are several reasons for their support [of the status quo]:

Economic dependence: The mining industry, and in particular cobalt extraction, represents an essential part of the Congolese economy. Around 70% of global cobalt production comes from the DRC, and millions of Congolese depend directly or indirectly on this sector for their livelihood. The DRC is dependent on this one industry. Reforms that could reduce the profitability or competitiveness of the industry may be seen as a threat to livelihoods and family incomes.

Local political and economic interests: Certain local political and economic elites benefit from the mining industry. Corrupt actors or those with ties to foreign mining companies may resist reforms that aim to improve transparency or redistribute industry profits more equitably, fearing that it will reduce their own profits or power.

Uncertainty about the effects of reforms: Some groups believe that proposed reforms – especially those aimed at improving working conditions, strengthening workers' rights or increasing taxes on mining companies – could discourage foreign investment and lead to a decline in production. This in turn could harm the local economy and job creation, especially in a sector where the workforce is already very vulnerable.

Lack of local consultation: Sometimes reforms are perceived as being imposed from the outside, without consultation or sufficient consideration of local realities. Local groups who benefit from the status quo may then feel disconnected from decision-making processes and fear that reforms will serve foreign interests more than they respond to local needs.

Resistance may emerge among those who benefit from the current system and who fear immediate economic losses or radical social changes.

The theme underpinning this seemed to centre around prioritising the short-term economics rather than a long-term transition plan for the whole country. Existing in this context, particularly as a researcher on agriculture, must feel suffocatingly heavy. I enquired how this history of exploitation in the DRC felt in her daily life.

Of course I notice it in my daily life, knowing, as a scientist, that we have the potential to be a rich country and yet languish in poverty. Often the question is whether these riches are a curse or a blessing for the DRC. Foreign powers target them and exploit them without thinking of the poor population. Living today in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and being confronted with the reality of mining, particularly of precious minerals such as coltan, cobalt, or gold, is a complex and paradoxical experience. On the one hand, there is a realisation of the geopolitical importance of these resources and their role in the global economy, particularly due to the demand for advanced technologies (phones, computers, electric vehicles, etc.). But this realisation is often accompanied by deep frustration.

Seeing a child starving in your presence and listening to the media only talk about the war in Ukraine and about helping their destiny… it leaves me perplexed. I often don’t know what to say or what to think in the face of this injustice. Aren't we humans too? Is our life not sacred like that of other peoples whose cries fill the international media? What have we done to humanity to deserve all this? Daily experience here involves these highly emotional questions.

There is also this tension between the pride of being part of a country so rich in natural resources and the suffering linked to the inability to benefit from them. For many, this situation creates a feeling of division, injustice and sometimes disillusionment with the state or global institutions, and a search for local or international solutions to redress the situation.

This is where research adds value. It can deeply impact a person, particularly if they live near mining areas like Kasaï, Katanga, etc., where environmental impacts are visible, where exploitation happens on a daily basis, but where the fruits of this work seem inaccessible. The question of mineral exploitation and its social, economic and ecological consequences thus becomes a key element of the experience of many of us Congolese.

The DRC has a long history of being extracted to build someone else’s wealth. 150 years ago, the people and riches of the DRC were violently exploited to make Belgian King Leopold II personally rich. His utterly brutal treatment of the country led to him being forced to hand the territory to Belgium as a colony in 1908, and it only gained independence in 1960.

The first prime minister of the independent Congo nation was Patrice Lumumba who campaigned for the independence of the Republic and fought against imperialism. He pledged to use the country’s rich mineral resources for the benefit of its own population. However, within six months of his appointment, author of Cobalt Red Siddharth Kara describes how he had been “deposed, assassinated, chopped to pieces, dissolved in acid and replaced with a bloody dictator, a corrupt dictator who would keep the minerals flowing in the right direction. So if you don't play ball with the power brokers at the top of the chain and with the Global North, Patrice Lumumba showed what's the outcome.”

Cobalt mining in the DRC began in 1924 with Belgian mining company Union Minière de Haut-Katanga, which now exists only as the original Belgian refining arm Umicore, written about by Ed Conway in Material World. The mining sector was nationalised in 1967. The state mining companies in the DRC came into financial distress in the 1990s, which led to them being reprivatised. This loss to the state was accompanied by radical austerity policies implemented by the IMF and World Bank, which was supposed to ‘spur economic growth and alleviate poverty’.

I wanted to ask Gérardine about this history, and whether these measures were still felt today.

Privatisation has had a considerable impact on the country's economy and exacerbated social inequalities. Many state-owned companies, particularly in the mining sector (such as Gécamines), have either been dismantled or sold off at low prices, often to the detriment of workers and local communities. Profits from mining, although substantial, have not been used to finance sustainable national development, reinforcing the feeling among a large part of the population that they have been deprived of their inheritance. What should have been ours has been lost.

Large multinationals, often seen as the main beneficiaries of this privatisation, are accused of exploiting natural resources without a fair redistribution of profits. This has fueled a sense of discontent and distrust towards economic reforms, which are seen as more favorable to foreign interests than to domestic needs.

Economic reforms accompanied by austerity measures imposed by the World Bank, such as reductions in public spending, tax increases, and cuts to subsidies, have also had serious consequences for the Congolese population. These measures have led to an increase in social inequalities, an increase in poverty and a reduction in public services, particularly in the areas of health, education and basic infrastructure. [Only] the minority inside the system which supports trafficking benefits from it. Many state-owned enterprises have closed, public sector wages have been cut, and economic growth has not compensated for growing social suffering. The reforms have contributed to political and social instability in the country, fueling protest movements and distrust of international institutions and the economic policies dictated by them. The population is tired of being dictated to by international institutions.

Mining continues to be a key sector, but profits remain largely captured by foreign companies, and the Congolese state is struggling to put in place effective mechanisms to redistribute the wealth generated, [meaning that they have no immediate effect].

Privatising the nation’s mining companies also marked a shift from state mining and corporate welfarism to private mining companies who practised minimally applied corporate social responsibility. The financial agreements the nations natural resources were sold off under were also later deemed unfair. They vastly underestimated the profitability of the mines. These contracts were entered into when the DRC was undergoing a period of economic and political instability emerging from a war.

The investors have also been accused of being uninterested in adding value in the DRC, such as through refining materials in situ. The lack of refineries means that there are fewer decent jobs and fewer resources to grow and diversify the country’s economy.

Thus far, frameworks aimed at improving responsible sourcing have been criticised for further marginalising artisanal and small-scale miners. Instead, they focus on alleviating the concerns of consumers in the global north rather than improving the welfare of miners and communities. Artisanal mining is the second largest employer in the DRC, and many argue that the key thing is to end child labour and exploitative practices, including evictions of whole villages on top of cobalt seams to places with much lower standards of living.

I asked Gérardine what local and national debates were happening around transforming the mining industry into a vehicle for sustainable socio-economic development.

One of the major debates concerns the way in which income generated by mining is redistributed. Currently, a large fraction of the profits goes abroad, particularly to multinationals, and there is little investment in local infrastructure, health and education. Discussions therefore focus on establishing governance mechanisms that would ensure a more equitable distribution of benefits. This includes proposals to strengthen mining taxation, fight corruption and ensure increased transparency for contracts and transactions.

The DRC needs strong and effective government structures to regulate the mining industry. This includes the establishment of strict regulations on [natural resource] exploitation, but also independent monitoring mechanisms to ensure compliance with social and environmental standards. Topics often discussed include training for public officials, the implementation of stricter legislation and the creation of a regulatory authority for the mining sector.

Mining in the DRC has been associated with serious human rights violations, including child labour and precarious working conditions, as well as armed conflict around mines and devastating environmental impacts. Current debates include proposals to strengthen the accountability of mining companies, particularly through international standards on the traceability of minerals and supply chains, as well as integration of sustainable development principles into mining contracts and use of technologies which pollute less.

These are huge conversations to happen in a deeply unequal society, and I asked Gérardine her own personal thoughts on a realistic and effective way to develop the mining sector.

For the mining industry in the DRC to become a real lever for socio-economic transformation, there are several concrete measures that should be put in place:

The creation of a strong local mining industry that works with local communities is essential. This involves public-private partnerships to develop on-site mineral processing and transformation infrastructure. Instead of simply exporting raw materials, the DRC could invest in processing plants that create added value and generate local jobs.

The mining sector should go hand in hand with strong education and technical training policies to allow local populations to directly benefit from the jobs generated by the sector. This includes training in specialised mining professions, but also in complementary sectors such as natural resource management, logistics, or industrial processing.

Mining companies should be encouraged or required to invest in corporate social responsibility (CSR) principles, including education, health, local infrastructure (roads, drinking water, etc.) and environmental protection. These commitments can be integrated into mining contracts and be part of the operating conditions.

The Congolese government must put in place stricter control mechanisms and ensure better governance of the sector. This includes implementing anti-corruption laws, strengthening the capacities of the National Agency for Mining Resources (l'Agence Nationale des Ressources Minières) and other relevant institutions, and creating transparency systems such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiatives (EITI).

The mining sector should move towards practices that minimise its ecological footprint (circular economy). This involves reusing extracted materials and recycling minerals, but also promoting clean technologies and the adoption of less environmentally-destructive mining techniques.

The mining sector must not be the only source of development. Economic diversification is crucial for avoiding the "resource curse", through investment in agriculture, tourism, light industry and services. This will help to stabilise the economy and offer populations a variety of opportunities.

It is not enough to exploit resources; they must be strategically valued to make the industry a real lever for sustainable and inclusive development for local populations.

Searching for a local battery industry voice, I spoke to Michel Shengo Lutandula, coauthor of a comprehensive report on the possibility of a battery industry in the DRC and Zambia.

The DRC and Zambia cannot do what the EU and US are doing, which already have competing factories. This will hurt them even more.

It will be necessary to go in the direction of developing specialized industrial ecosystems to move from the status of producers of raw materials to that of producers of batteries or their components. All efforts must therefore contribute to the emergence of a local industry of batteries, endowed with an African dimension, and battery components in which other nations of the world would bring their know-how, expertise and investments.

I asked Michel for his take on Apple’s plan to use only recycled cobalt from 2025, and whether he thought it was a way of avoiding engaging with the problems in the DRC.

I do not think that the dispute between Apple and the DRC is the main justification for using recycling of critical metals as a means of supply by 2025. There is also the fear of a sudden breakdown in the supply chain because it is in the hands of relatively unstable countries and also, the fact that more emphasis is being placed on R&D by industrialised countries to find cheaper alternative resources and thus escape their dependence on these critical metals.

However, it is true that the ever-growing global demand for critical metals will be so great that primary sources (mining resources), they alone will no longer be able to satisfy it so that alternative sources, particularly secondary resources from the recycling of critical metals, must be used. The growing demand for these battery minerals will further amplify and accelerate the mining of primary resources and also boost the use of secondary resources, including recycled critical metals.

This point on supply chain resilience is an interesting one, and something I’ve heard a lot in conversations about recycling battery minerals in Europe. Particularly in an increasingly hostile global climate as well as political climate, having access to your own mineral supply is a huge advantage. A lot of this conversation boils down to a matter of control - both of mineral supply chain and the humans upon which it depends.

Gérardine reflected on the DRC’s place in this supply chain web of global politics, where everyone wants Cobalt.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is at a strategic crossroads in the geopolitical competition between the United States, China, and other global powers, particularly because of its vast natural resources of cobalt and copper in particular. In this context, to avoid becoming a mere pawn in this great rivalry and put the well-being of its people at the heart of its priorities, the DRC requires an ambitious political and economic approach, focused on empowerment, smart diplomacy, and deep internal reforms.

In this context, I asked her whether it would be enough for the DRC to take control of its own mineral supplies again and domesticate a refining industry for cobalt and copper.

This is an essential step for the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) towards greater economic autonomy and increased control over its natural resources. However, for the DRC to truly become a “Free Congo” in the full sense of the term, several other political and economic dimensions will also need to be addressed.

Control over natural resources will not be enough without a strong institutional framework. This includes i) fighting corruption. The DRC is often ranked as one of the world’s most corrupt countries. A thorough reform of public administration is necessary to ensure transparent and efficient management of resources. ii) Protecting property rights, combating abuse of power, and establishing impartial judicial mechanisms are all crucial for establishing a stable and predictable environment. Establishing stable and attractive economic policies, while preserving national interests, will maximise the benefits of the mining sector while minimising the risks of harmful foreign exploitation.

The mining sector represents a disproportionate share of the Congolese economy. An economy that is too dependent on raw materials remains vulnerable to fluctuations in global prices. The DRC will need to invest in other sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing, or services to reduce its dependence on minerals and create sustainable jobs. It will need to develop infrastructure (transport, energy, telecommunications) to support the diversification of the economy.

The DRC must also invest in education and training needed to improve the skills of the population, particularly in the technical and industrial sectors, in order to strengthen the country's competitiveness.

Internal conflicts, particularly in the eastern provinces, which undermine the DRC’s political stability. Peacebuilding, strengthening national unity and resolving internal conflicts are essential to ensure an environment conducive to economic development.

A profound transformation is necessary for the DRC to become truly sovereign, prosperous and stable, with strong institutions that promote the well-being of its citizens and ensure sustainable development.

It’s a tough ask, to demand all of this of one of the world’s poorest and most unstable countries. It’s clear that reforms must be driven by communities in the DRC, but as industries which depend on these metals for our clean energy transition, we must ask ourselves how best to support this transformation from the sidelines.

Using recycled metals in a circular economy is a very good aim, but these metals all came from somewhere in the beginning. Creating refining capacity in the DRC would be a good start to ensuring that some of the country’s wealth stays there.

I’m left with a lot to reflect on, and I’d like to thank Gérardine and Michel again for painting this deep picture of a minerally rich country in poverty. Gérardine is currently putting her considered recommendations into practice and developing an ecological farm in Kinshasa. She wants to use regenerative agriculture to transform her community. The project aims to produce organic and local products as well as training 5,000 local women and young people over 5 years. You can follow their journey on LinkedIn to support and stay in touch with life in the DRC.

🌞 Thanks for reading!

📧 For tips, feedback, or inquiries - reach out

📣 For newsletter sponsorships - click here

🌐 Follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, and our website

ND-GAIN index summarizes a country's vulnerability to climate change and other global challenges in combination with its readiness to improve resilience. In 2022, when DRC was fourth, the countries worse off were Eritrea, Central African Republic and Chad. The least vulnerable country in the same ranking was Norway.