With Li-ion battery prices hovering above the mid-two-digits in terms of $/kWh, what are the knock-on effects on the circular economy that the EU is trying to build around this technology?

Today’s writer Lorenzo is the owner and lead consultant at Teraton, a boutique consulting company focusing on batteries and energy storage. He caught the lithium fever after assembling his first LFP cell using polymer electrolytes in 2009, and has since been part of the battery industry in various capacities in three countries, from academia, to technical consulting, to automotive and energy storage R&D roles.

The European Union has been playing catch-up on battery matters with China through its Battery Regulation, parts of which entered into effect in mid-2023. In it, the EU has included several provisions to make sure battery manufacturing becomes a circular industry, where critical materials are sourced and – most importantly – reused responsibly. Such provisions include due diligence practices, recycling targets, as well as pathways to prepare mildly degraded batteries for a “second life”.

Second life batteries mostly refer to the reuse of high-performance EV batteries into less demanding applications at lower depth-of-discharge and C-rate operation. Traditionally, the figure of merit that has been used to deem a battery unsuitable for first-life applications is when it reaches 80% State of Health (SOH), that is, when only 80% of its original capacity can still be released during discharge.

At 80%, a battery’s internal resistance is around twice as high as it was at 100% SOH; it is thus thought that EV owners would be unwilling to put up with a lower charging efficiency and lower driving range, and sell/scrap their vehicle. While there is little evidence in consumer behaviour to confirm this assumption, it is true that, below 60% SOH, performance degradation ceases to be linear and undergoes a rapid and abrupt decay down to 0% SOH.

Industry stakeholders are hopeful that a “second life” is possible between 80% and 60% SOH, perhaps by limiting the current that is drawn from those batteries and by reducing their depth of discharge.

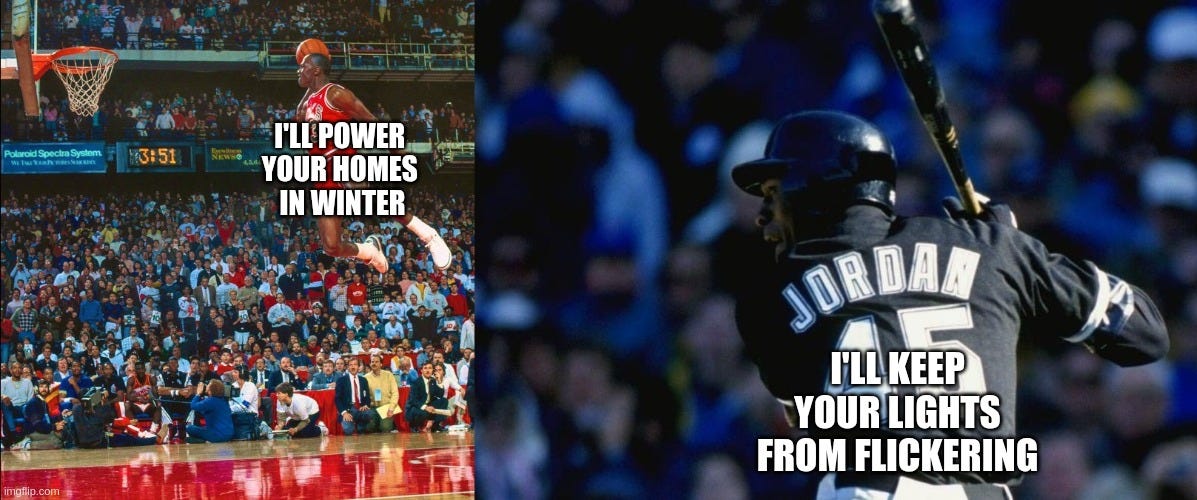

Second-life batteries, then, are basically the equivalent of Michael Jordan’s first retirement from the NBA in 1993 to join Minor League Baseball.

The EU is trying to foster the repurposing of all these electrochemical MJ’s by means of Article 73 in the Battery Regulation, which lists three conditions to turn a spent battery into a new usable product. Other international standards have also been put in place, like UL 1974, IEC 63330, and IEC 63338, to better define the conditions around battery repurposing.

Unfortunately though, there are forces at play that, much like the Monstars in the movie “Space Jam”, are trying to bring His Airness back into the court; these five otherworldly forces at play are conveniently illustrated below:

Lack of OEM data

Second life batteries come “as is”, with minimal involvement from OEMs, who effectively consider them a liability more than an opportunity. After all, aged batteries are out of warranty, can damage a brand’s reputation if they catch fire, and can be reverse-engineered for hacking purposes.

Each battery pack is equipped with a proprietary BMS that is virtually inaccessible without a so-called .dbc file, a document that decrypts the hundreds of signals stored within the BMS. OEMs actively refrain from sharing this document with third parties, as it could be used for malevolent purposes. Batteries can be freely accessed through the OBD port, which yields an aggregated subset of the full set of BMS data. Here you can find valuable information like the SOH, but since this value is usually inferred and not measured by the BMS, testing needs to be carried out to validate it. Once again, OEMs have no interest in sharing the algorithms they use to get to the SOH value.

Expensive logistics

Batteries are expensive to move around by freight, and in places like Europe they need to be transported across borders under the supervision of local authorities and ADR rules, the international regulation on transportation of dangerous goods.

Some second life batteries may turn out to be too deteriorated to be repurposed, which effectively means any shipment carries deadweight that needs to be disposed of upon arrival. All those modules and packs could be tested and selected before shipping, but two conditions must be met: you need testing equipment and you need qualified personnel to carry out those measurements - not quite something that is readily available at a car dealership or a scrap yard.

Low resale value

With Li-ion cell prices hovering above the mid-two-digits in terms of $/kWh, this is practically pushing used batteries’ resale value well into the low-two-digits. This is great for repurposers, but who is going to enter such a low-profit margin segment as a marketplace or intermediary? Those batteries may as well go straight to recycling at that price point.

To prove that, let’s do some back-of-the-envelope calculations here using BNEF’s latest data (shown above): in 2024, a brand new battery pack cost 115 USD/kWh; let’s say it can last for 3000 full cycles until it reaches about 80% SOH, and then another 1000 cycles before hitting a critical 60% SOH. Anyone trading in a used EV pack at 80% SOH from, say, 2018, paid almost twice as much back then on a per kWh basis, and yet can only expect:

from the sale. That is a drop in value by more than 80%, mostly driven by the spectacular cost improvements achieved by battery manufacturers in China since that 2018 EV was placed on the market. The value indicated above is at cell/module level, and does not take into account the purchase of a dedicated BMS (remember, we cannot use the original one), new wiring, ancillaries, labour costs, etc.

As the cherry on top of the cake, a new battery comes with a 10-year warranty, which the used battery cannot offer, on account of the warranty being voided the moment the pack or module was removed from the EV.

More refined techno-economic analyses can be carried out, but the main contributing factor in determining the resale value of a used battery is still represented by how cheap newly made cells are getting.

Recycling targets

Speaking of recycling, the EU has set ambitious targets in terms of battery recycling rates, and in an exponentially growing market this can only mean one thing: used batteries are more valued as feedstock for recycling processes than as electrical components.

Better, cheaper new batteries

Finally, technical advancements are pricing used batteries out of the market, as old EV pack architectures become obsolete and OEMs are able to pack more energy per unit weight and volume in their new cells. New form factors, new chemistries, more advanced safety systems, as well as innovative battery management systems accelerate the planned obsolescence of batteries that were air-cooled and meant for price-insensitive early adopters. A 29 $/kWh 8-year old battery is in direct competition with a 50 $/kWh brand new battery coming from China. Can those second life batteries still be considered “cheap and good enough”?

Will this be a Space Jam for the second life battery industry? Not all hope is lost; geopolitical tensions are as rife as ever, and the situation may change if tariffs and export bans are put in place that disrupt the supply chain. A sudden scarcity of LIBs in the West may lead to a rush in digging out spent batteries from warehouses and unsold EVs to fill some gaps in the demand curve.

Let’s not forget as well the long game the EU is playing in terms of critical mineral sourcing: the goal is to retain as many of those minerals within the EU as possible. Some analysts believe many used EVs will flock to developing countries to be driven there, but it may very well be the case that they will instead turn into inexpensive feedstock to meet European battery recycling targets.

Finally, there is no need for a direct competition between first-life and second-life batteries: a number of niche markets exist where volumes are too low for battery companies to even notice, and where cheap, widely available used batteries could provide a quick go-to market strategy. This is the case for EV retrofitting, EV repair, some off-grid use cases, and rapid prototyping.

If those markets look too elitist and more like a proper retirement sport to you, go ask MJ which career he picked last.

🌞 Thanks for reading!

📧 For tips, feedback, or inquiries - reach out

📣 For newsletter sponsorships - click here