New from Old: Start Ups in Recycling part 1

What will it take to get to a circular economy in batteries? Issy takes a look at two early movers in the UK recycling industry.

There’s a lot of public doubt about whether we have the technology to recycle batteries. The general perception among the public in Europe is that lithium-ion battery recycling is “not going particularly well” whilst the truth is the best recyclers are able to recover 80-99% of nickel and 90-99% of cobalt.

Focusing on the economic challenge, there currently isn’t the volume of cells coming from end-of-life vehicles for large scale plants to be able to run at a good profit margin. Jannis went into detail about this in Bigger, better & faster circular’:

‘In order to be profitable long term, the large plants must be operated at full capacity now and in the future.’

You can see the challenge in this left graph from the Fraunhofer Institute, as between 2025 and 2040 the increase in decomissioned lithium ion batteries is projected to be exponential. Predicting and timing plants to open when that demand is there is difficult.

Currently, most batteries are recycled outside of Europe in Asia. Within Europe, we have two current problems. The volume of end-of-life batteries is currently small, and because of this extracting all substances is not profitable, hence recovery efficiency is lower than in China and South Korea.

However, this is all set to change with the shifting focus on domestic supply chains. A key underutilised source of minerals is those we can recycle out of old batteries. In a young industry in Europe, this gives huge first mover advantage to those who can do it first, and well. We spoke to two really interesting companies in the UK trying to solve two particular recycling challenges: wastewater and black mass, to get their takes on being early in the game and where they saw themselves going. This first part focuses on wastewater.

Watercycle Technologies

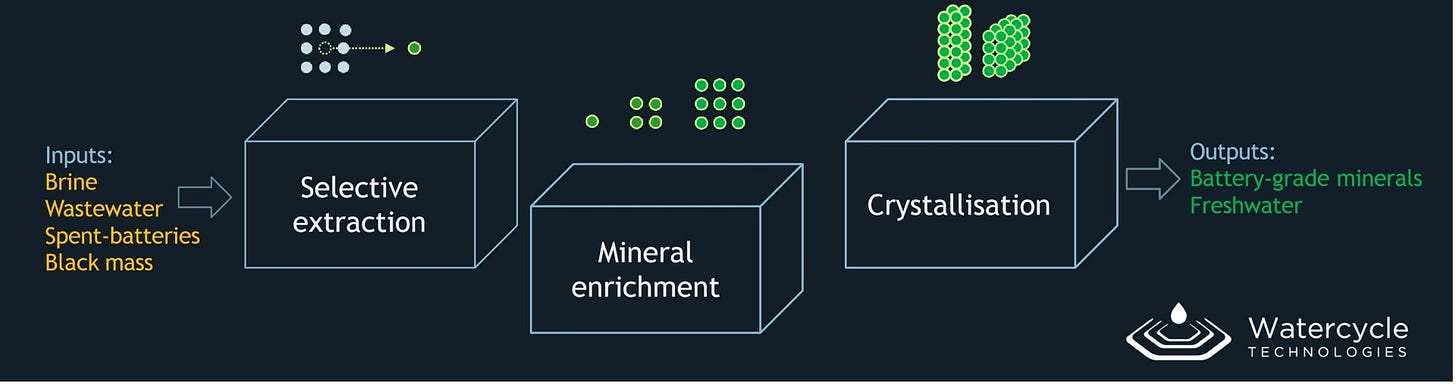

Watercycle Technologies is a spinout from the University of Manchester. They design and build end to end mineral recovery systems capable of extracting high-purity products from a wide range of inputs, including geothermal brines, end of life batteries and industrial wastewater. The company closed a $5.6 million Series A round at the end of November.

Their focus is solving water scarcity, mineral scarcity and environmental pollution simultaneously. The modular 3 stage process inputs brine, wastewater or spent batteries and turns it into battery grade minerals and freshwater. They have built a pilot system capable of treating black mass and brine, and have produced over 100kg of battery grade lithium carbonate so far.

They say that this way of treating lithium brine enables a 10x reduction in CO2 emissions compared to hard rock lithium mining, and can save 500m3 of water per ton of LiCO3 compared to conventional evaporation process, giving it a sustainability advantage over both.

The aim is to offer an industry agnostic solution: simply that if wastewater is being produced, it can be treated and be profitable.

We spoke to cofounders Dr Seb Leaper and Dr Ahmed Abdelkarim to understand their business and thought process.

How do you think about Watercycle’s place in the wider ecosystem of sustainability?

It’s a bit complicated - we are trying to find a balance between being market leaders in lithium extraction but also to still keep that association with different industries such as desalination and other types of wastewater. We book-end the supply chain, so provide both the primary mining processing as well as recycling and wastewater management.

Our job is to recover minerals and produce freshwater. We see ourselves as a mineral extraction company, providing a general platform for mineral extraction from different streams from liquid and solid waste.

Recycling is still quite an early industry in Europe - and water is an especially hot topic - what advantages and challenges does this bring?

One advantage is definitely understanding the market very early. The early adopters are our customers which is a good playground for testing and scale up.

There are some other companies in this space. We essentially want to be the first to be second in order to learn from their pitfalls and struggles. We are trying to asorb lessons from everyone else on what they’re not doing and address the painpoints in the technology. Part of this is working with other battery recyclers to help them purify the things they struggle with. Through one lens, they’re a competitor but actually they’ve become a partner as we can do the stuff that they can’t. Our multi-mineral approach was good strategically and being able to treat both liquids and solids allows us to maximise the advantages of waste.

The true cost of water discharge is often not factored into battery recycling. We think about it as every atom must be saleable, recirculated into the process or compliantly discharged. This means that every byproduct generated is a potentially saleable product and we have to do what’s needed to get it to be saleable.

Is there a responsibility on early movers to lay any kind of ground work in pushing for regulation?

Previously there has been a ‘commercialise a product now, worry about consquences later’ attitude, which is easy for consumer products but not possible for this kind of industry where the consequences are potentially enourmous. We’ve already seen with fluorinated products and PFAs which are really difficult to process in their low concentrations in wastewater, with devastating consequences.

Our approach instead is not to let it get into the discharge, as once it gets out it is hard to process in a much less concentrated form. To that end, we are really trying to be as exhaustive as possible, particularly as battery recycling is hazardous. The chemistry here is complicated due to the mixtures of battery chemistries and large possibilites of side reactions. The early movers need to be diligent and map out all the possible risks to safety and the environment, and we do a lot of work trying to understand that and supplying it to the Environment Agency.

Is there an advantage to being a modular based technology when it comes to raising funding - how have you found the response to the scalability of your technology?

A lot of climate tech companies don’t make it past Series B funding round as the capital costs involved are too high. They find themselves in a gap where they are not yet ready to convince a bank to give debt, since you need first versions of your technology functioning to prove to a bank you are ready for investment. By having modularity we achieve two things: it lowers the barrier to entry to customers and for us it keeps capital costs under control using a few hundred thousand rather than millions. Our pilot system was built for £150k, and it’s a little rough round the edges but capital efficient. We had to learn very early how to build these machines out of nothing right away.

We work with the mentality that modularity works, since we have already achieved this before and we know how to deploy again. It was difficult in the beginning but this experience is in our favour as we can build our systems that function well for low capital costs. If you can prove a process to be economical at a small modular scale, then it will become even more economical at higher scale. This all requires partnerships as getting hold of the feedstock is very important.

We try to take a combination of UK approach which uses the maximum ability of minds and money to achieve as much as possible as well as the US mentality of pushing to do lots at once, albeit with less capital. We closed a Series A round, and we feel very positive as we are producing material, building systems and signing contracts.

🌞 Thanks for reading!

📧 For tips, feedback, or inquiries - reach out

📣 For newsletter sponsorships - click here